How to Build a Personal Website

TL/DR

How to build and host a personal website. For free.

Should you make a personal website?

- Yes.

Static or dynamic?

- Static if you want it easy, quick and affordable.

- Dynamic if you want it interactive and you want to store things. This guide focuses on static websites, which are ideal for portfolios, blogs, and marketing pages.

Setting up your site:

- Install necessary software: Ruby, Jekyll, Bundler, Git.

- Choose a theme, here: Chirpy, a free Jekyll theme.

- Clone the theme’s repository and install dependencies.

- Personalize the site using the _config.yml file (title, URL, etc.).

- Add content using markdown files in the _posts directory.

- Hosting the site: Using Github Pages, a free service that allows you to host your static website.

Additional points:

- How to create an “About” tab

- How to create and add a CV using markdown

- How to add a favicon

- How to add comments

- How to check site traffic using Google Analytics

- Troubleshooting common issues

Why Build a Personal Website?

Say you are a student with a clear goal in mind of where you want your career to go. You are working towards becoming an autonomous systems engineer. That means continuously learning about a vast amount of topics in a self-reliant way. It means making experiences. It means communicating with your peers. And it means gaining technical proficiency in many different fields of engineering.

First Impressions

All of the above can be showcased brilliantly on a personal website. What better way to make a first impression, than, instead of sending your CV to the company of your dreams in paper (I live in Germany. This is a likely scenario.) or email form, simply sending them a link to your own personal website? It will create a much clearer picture of you. Of course there’s LinkedIn etc., and LinkedIn is a nice way of presenting yourself, but to present a much more in-depth view of who you are, what you are learning and what you are good at, a personal website has so much more potential and room for moving about in.

Documentation

You can use the website to keep track of what you are currently working on or learning. This is not only a great way for you to remember and look up things at a later stage yourself (this post is also partly documentation for me). You are also helping others that may be struggling with the same topic. And as an added bonus, you are showcasing all of your learings and workings to future employers.

Blogging

Holding onto past experiences not only has great nostalgic value (see my Ecurie Aix post), it also provides the possibility for you to give a more indepth view of past experiences you have made, be it during your studies, extracurricular activity (such as student competitions, nudge nudge, hackathons, internships, excursions etc. ) or simply holding onto things you have learned. And in this case I don’t mean technical things (that can go into documentation), but rather about soft skills or things you find important to remember in your day-to-day work or student life. Once again, LinkedIn can provide a good platform to write articles as well. But on your own website, you can, a) go very in-depth and apply beautiful formatting (e.g. using Markdown) and b) the article is more “your own” than if it is uploaded onto a third-party platform. While I might use LinkedIn for shorter posts, anything elaborate will land on my personal website.

How to Build a Personal Website

To start off, I am not a web developer and by no means an expert. I am conveying how I built my own personal website and I think it came out quite nicely. I would also like to elaborate on how I solved the problems I faced. While there are many platforms to easily create websites in a “drag-and-drop” sort of fashion, these typically come at a price. Therefore, I decided to go a different route using technical knowledge I had.

Static or Dynamic?

The first thing you need to choose is if you would like to create a static or a dynamic website.

This site is static. Feel free to take a look around and see what it can do!

Static Websites

+ Ease of implementation

All that needs to be done to get a static website up and running is to host some HTML and CSS source code on a web server. That may sound daunting, but it really isn’t, you will see!

+ Cheap

Static websites are cheaper to host. This one is hosted for free on GitHub Pages (more on that later).

- Limited Interactivity

The website’s data is stored on a webserver as-is. If a user opens this website, this data is simply retrieved and presented to them. This post, for example, will be taken from my GitHub account and presented in exactly the same way to each user. Therefore, a static website largely runs without any background computations going on on the server.

- Any changes to the website must be made directly in the websites source code, as I am doing by writing this post. Some knowledge of this is therefore necessary, but that’s why we’re here, right?

- Therefore, static websites provide limited interactivity, apart from e.g. links and buttons. Things like comments or forms can also be added with third-party services (also more on that later).

Common Types of Static Websites

- Portfolios

- Blogs

- Marketing pages

Dynamic Websites

+ User Specific Display

Dynamic websites are built on the server when a request comes in. That means that they can be displayed to different users in different ways, depending on, amongst other things, where they live, their language settings or what time it is. It also means that user specific content can be displayed.

+ Database Access

Dynamic sites can access databases. This might be especially useful for online shops or social media platforms that need to store data about items, users, orders etc.

+ Interactivity and Functionality

Dynamic websites allow server-side scripting. This means they can implement functionalities, so called web-apps, such as e.g. processing the aforementioned database data or user input. This might be a social media site or an online function plot generation tool, pretty much anything you can program.

- More Complex to Implement

In order to implement this functionality, the single developer must know how to actually do frontend and backend development. This includes HTML, CSS, JavaScript or similarly for the frontend design and functionality, and e.g. JavaScript or PHP for backend development, along with SQL to work with databases. For me, who didn’t need a huge amount of functionality and wanted to set something up fairly quickly, this is a reason why I chose to go for a static site. But who knows what the future will bring.

- More Expensive

If you prefer getting around the required knowledge to set up a dynamic site yourself, website builders such as Wix exist. However, those often come at a cost. Furthermore, dynamic websites tend to be more expensive to host.

Most Common Types of Dynamic Sites

- E-commerce platforms, such as Amazon

- Social media platforms, such as Instagram or LinkedIn

- Booking and reservation systems

- Streaming sites

How to Create a Static Site

In this post, I will show you how to create a portfolio website like this one using Ubuntu Linux. As mentioned, this is a simple static website. It works on the basis of Jekyll, a static site generator. It takes in your data and turns it into an actual site. Thanks to the community, different so-called themes for the site are available for download. This means that someone already created a template that looks and behaves a certain way, and all you have to do is customize it to your liking and adding your own data. This is also the path I took as a web development noob. Feel free to take a look at some themes over at GitHub.

In the following, I will show you how I created my Jekyll website on the basis of the Chirpy theme, but many of the following steps apply to other Jekyll themes as well, check out their respective documentations for specifics. Some basic knowledge of Git and GitHub will be required, so if you have never heard of these things, or need a refresher, check out the GitHub Documentation.

Finally, this is by no means an extensive documentation of all the building blocks needed. It will get you up and running and dressed nicely, but it is by far not the entire wardrobe. So once you are done with this tutorial, go check out the documentations I have linked to up your game if you like!

Getting Started

All of the steps I will show you in the following can also be found on according documentations, such as Jekyll’s documentation, that of Git, or Chirpy. I will link those wherever appropriate. Here, I will give you step by step instructions of how to do all of these things, all in one place 😎. I will also provide a few details in case you’re interested, but feel free to gloss over them. To begin, we need to install a few things.

- Ruby, and other dependencies

As Jekyll is implemented in the language Ruby, this needs to be installed first. Check, if you already have it installed, and the version:ruby -v. To install or upgrade, simply execute1

sudo apt-get install ruby-full build-essential zlib1g-devThe

build-essentialpackage contains sub-packages, such as the GNU compiler collection (gcc) or the build automation tool make, among other things. Thezlib1g-devpackage includes files needed by applications that use zlib for compression and decompression, which apparently, Jekyll does.

Ruby software packages are called gems (at least if they are distributed through the RubyGems package manager, which is installed along with Ruby). Jekyll is such a gem. However, take note that gems should never be installed as the root user (i.e. usingsudo gem install ...). You could end up installing a malicious gem which now has root access. It could wipe out your entire hard drive if you’re unlucky! Therefore, you should always trust blog posts on the internet telling you what to do instead, which is: set up a gem installation directory for your user account. To do that, perfrom the following commands:1 2 3 4

echo '# Install Ruby Gems to ~/gems' >> ~/.bashrc echo 'export GEM_HOME="$HOME/gems"' >> ~/.bashrc echo 'export PATH="$HOME/gems/bin:$PATH"' >> ~/.bashrc source ~/.bashrc

Jokes aside, that is actually what the Jekyll documentation tells you to do as well, so go ahead!

- Jekyll and Bundler

While Jekyll is the actual static site generator, bundler is a tool that makes sure that you always have the gems and their correct versions installed to use a Ruby project, which is what Jekyll is.1

gem install jekyll bundler - Git

Git is a version control system you have probably at least already heard of (at the latest earlier in this post). It allows people to work on code together, or distribute code to one-another, just like the nice people that created the Jekyll theme we will use distribute that code to us. If you are entirely new to Git, check out the aforementioned getting started on GitHub. Otherwise, you probably already have it installed, otherwise run:1

sudo apt install git-all - Chirpy Theme

And finally, we need to install the actual Chirpy Jekyll theme, which provides us with a template upon which we can build our site. It provides all the files Jekyll needs to generate our static site, and we can add and modify it to our liking. So let’s see how to use this and get started with our actual site!

Setting Up our Site

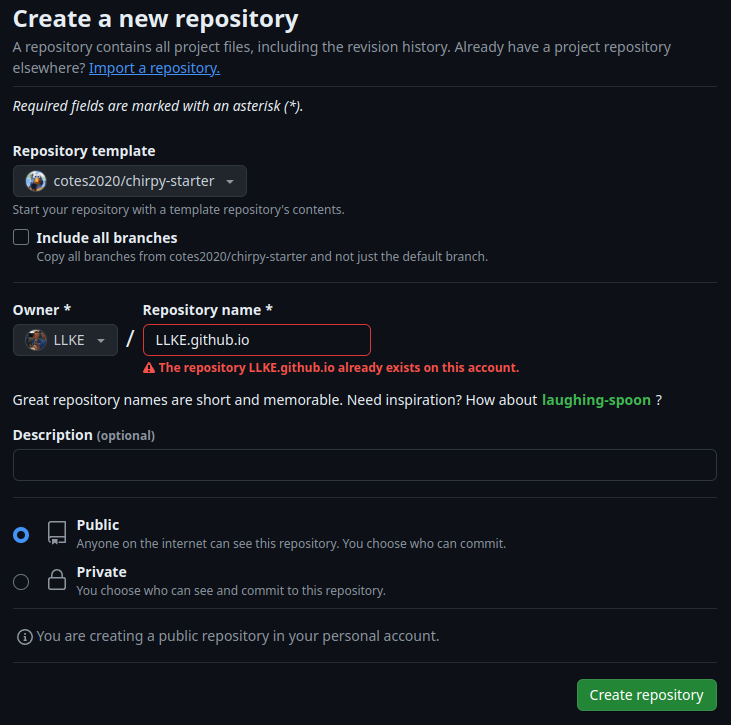

We will be using the Chirpy starter to create our site. The way that a Jekyll site is handled, is that we create our own GitHub repository, based on the Chirpy Starter, where we can then edit the template as we like. The way to do that is to head over to the Chirpy starter link from above, scroll down to “Installation”, and click “use this template”. You will be prompted to create a new GitHub repo.

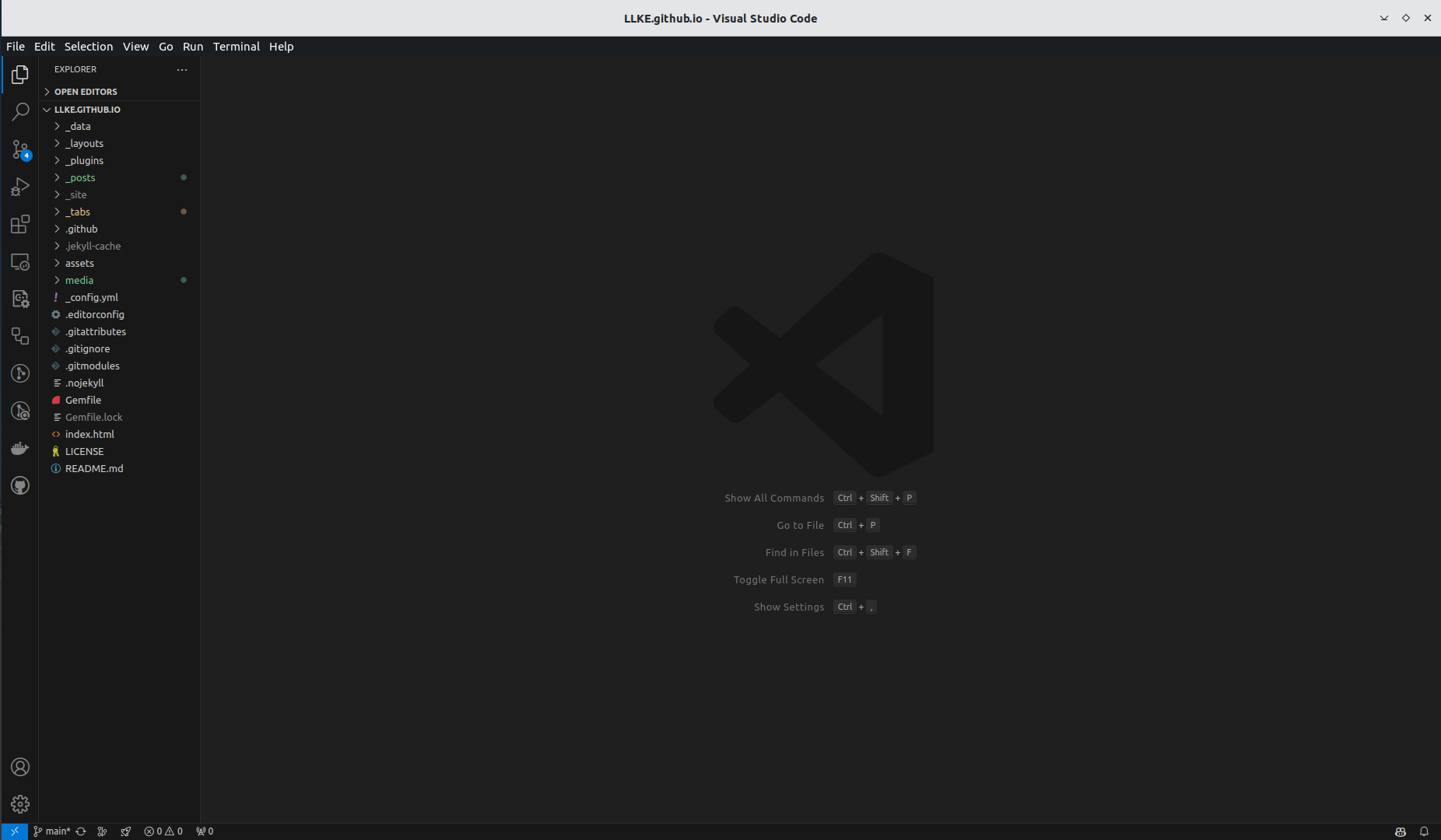

As the Chirpy Starter suggests, you should name your repository USERNAME.github.io in the provided field, where USERNAME is your GitHub username. It is a good idea to do so, we will later see why. Also make sure that the repository is public. This becomes important at latest if you want to deploy your site. Now clone that site to your local machine (again, see the GitHub on how to do that). Then open the cloned repo in the code editor of your choice, e.g. VSCode. That should look something like this (without the _layouts folder):

Now we need to install dependencies for this site. That happens to be very straightforward, as earlier, we installed Bundler on our system. This is exactly what Bundler is there for. Go ahead and run

1

bundle

in your console. That should install all necessary dependencies. Now you are basically good to go. Run

1

bundle exec jekyll s

This will serve the site on your localhost (i.e. only on your local machine, not publicly). The according IP should be shown in your terminal, something like http://127.0.0.1:4000/. Open that in your browser. And there you have the very first (not yet personalized) version of your future website!

Personalizing our Site

Within the repository you cloned, there is a file called _config.yml. This is the place to start. This is where we set some configurations for the website, e.g. time zone, if you would like the light or dark theme, and where your profile picture can be found. Let’s start with the basics.

Language and Time Zone

To set the language of the site, check out the link provided in the _config.yml file. I have my site set to english, which looks like this:

1

2

3

4

# The language of the webpage › http://www.lingoes.net/en/translator/langcode.htm

# If it has the same name as one of the files in folder `_data/locales`, the layout language will also be changed,

# otherwise, the layout language will use the default value of 'en'.

lang: en

The same goes for the time zone. Check out the according link provided to find out what time zone you are in.

Title and Tag Line

On this site, the Title is “Laurens Keuker” and the tag line is “Aspiring Autonomous Systems Engineer”. Go ahead and choose something catchy.

URL

This is the URL that your site will be hosted on later. Of course, you can host it wherever you want, but if you want to tag along with me and host your site on GitHub Pages (which is an easy and free way to host your site), change it to "https://USERNAME.github.io". For me, that looks like:

1

2

3

# Fill in the protocol & hostname for your site.

# e.g. 'https://username.github.io', note that it does not end with a '/'.

url: "https://LLKE.github.io"

You can also add your GitHub username where the _config.yml prompts you to do so.

The following points are optional, not everything in the _config.yml needs to be filled out. If left blank, they will simply not appear on your site.

Adding a Profile Picture

Search for the avatar: prompt. This is where you tell Jekyll where it can find your profile picture. First, add the picture to the “media” folder within the repository. Then link to it in the _config.yml file by specifying its path within the repo:

1

2

# the avatar on sidebar, support local or CORS resources

avatar: 'media/<image name>.jpg'

Author and Socials

Fill in the author field according to who you would like to be displayed as the author of your posts. Also uncomment (i.e. remove the #) the social media links, which you would like to share on the website. This is the link that the reader will be re-directed to when clicking on the author’s name. In my case, I link to my “About” page, but you could also link to LinkedIn, GitHub, anything you’d like.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

social:

# Change to your full name.

# It will be displayed as the default author of the posts and the copyright owner in the Footer

name: Laurens Keuker

email: laurens.keuker@gmail.com # change to your email address

links:

# The first element serves as the copyright owner's link

- https://llke.github.io/about/

There are a few more things you can modify. Feel free to adjust and tweak as you see fit. I will also go more indepth on how to add comments to posts a bit later.

Hosting our Site

Now that we’ve customized our site to our liking, of course we need to host it (i.e. upload our changes and actually make it accessible through the internet). As mentioned, we can do this using a service GitHub provides, called GitHub Pages. In short, we upload the changes we made to our website’s files locally to our remote GitHub repository, and … that’s basically all we have to do. GitHub does the rest for us, as it now has all the files it needs to generate the site. But one step at a time.

I’m sure most are familiar with the Git workflow. If you are, just stage, commit and push the changes to your GitHub repo, GitHub will perform the according GitHub Actions needed for deployment. Once those have run, you should be able to access the site from the URL you provided! (i.e. https://USERNAME.github.io). You can also see where it was deployed to in GitHub itself. Open the repo, and in the right side bar, there is a section called “Deployments”. Click that, and GitHub will display the URL.

For those not familiar with the Git workflow, I will provide a summary here.

Open a terminal (or use the already opened one) within your site’s root directory on your machine (something like USERNAME.github.io). You can either do that by opening your documents, navigating to the directory, right-clicking and selecting “Open in Terminal”. Or you can open a terminal directly and typing

cd ~/path/to/USERNAME.github.io.

Type git status in the terminal. This will show you what you have changed. In our current case, this should show something like this:

1

2

3

4

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: _config.yml

As you can see, Git points out that we have changed the _config.yml file, as we adjusted some parameters. Next, type git add .. This makes Git stage all of our changes. Finally, type git commit -m "Initial adjustment of site configuration parameters.". This commits the changes, meaning git takes a “snapshot” of the current state of your code, including a short summary of what you changed (this can be anything you like, but it should be descriptive). Now you are ready to push the changes you made to the Git repository on your local machine to your remote GitHub repository, i.e. upload it to GitHub. To do that, simply type git push. If you open GitHub now, you will see that the changes have been added to the according repository.

Now all you have to do is wait a short while, while GitHub deploys your site to GitHub Pages. Once that has happened, GitHub will display a green check mark in the right sidebar under “Deployments”.

Go ahead and enter the URL you selected in your _config.yml. You should now see your page!

How to Create a Post

Now that website would of course be entirely devoid of content, so I will now show you how to create similarly amazing content as I do. In your site’s directory, there is a folder called _posts. This is …drum roll… where we can write posts. If we then once again push our changes to GitHub, these will be displayed as posts on our website.

Now posts are written in Markdown. Check out this cheat sheet if you are unfamiliar with writing markdown, but it really isn’t difficult. It’s basically plain text with some syntax you can use to format your text, add pictures, headings, links, code, most things I also added to this post. When building the website, it is rendered to HTML and displayed in a very nice way.

So, to get started on your first post, add a new markdown file to the _posts subfolder. It’s name must be formatted as: yy-mm-dd-<name>.md. This is important, otherwise it will not be recognized. This post, for example, is internally called 24-05-28-website.md.

Next, we need to add a header to our post. This contains metadata such as the layout used, the title, a banner image and a date (the +200 signifies the time zone of the according time). It can also contain categories and tags, where categories will be listed in your site’s sidebar (the first is the main category, the following are sub-categories), and tags work similarly to hashtags on other platforms, where posts can be referenced by them. Tags should all be lower case. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

---

layout: post

title: "How to Build a Personal Website"

date: 2024-05-28 12:00:00 +200

categories: [Tech, Tutorials]

tags: [website,tutorial,markdown,jekyll,ruby]

image:

path: /path/to/banner.png

alt: Banner

---

Adding photos to your post is also easy. Simply place the photos you would like in the media folder of your site. I like making a subfolder for every post I create. You can then reference them in your text by typing:

1

Placement and size can also be controlled, see the documentation for details. The “Alt Text” is displayed if an image doesn’t load for a user for some reason. It is also used by search engines to understand what the picture is about. Therefore, choose wisely.

Finally, to add post sharing capabilities, head over to _data/share.yml. Simply uncomment those plaforms on which you wish for people to share your content, or add new ones the by following the format there. You can find icons for pretty much any brand you can think of over at Fontawesome. Simply copy the name of the icon into the according spot, e.g. icon: "fa-brands fa-linkedin".

That’s pretty much all you need to know about creating posts in markdown. I’m excited to see what you will create!

“About” Tab

Take a look at the sidebar of this website. You will see an “About” tab. As the name suggests, here you can present any information about yourself, your company or whatever the website is for. As this is a tutorial on how to create a personal website, I will show you how to create a page about yourself, just like I have done.

It is actually very simple. Navigate to the directory _tabs in your site’s directory. Here, you will see a markdown file for each tab that already exists on your page, except for home, which is used to display your most recent posts. Open the about.md file. Currently, there’s not much in here. Let’s change that.

Head over to the ProfileMe page. It is a page mainly designed to create a pretty GitHub landing page for your profile, just like mine.

Side Note: Follow the instructions on ProfileMe to also freshen up your GitHub landing page. It turns your profile up a notch.

This page generates a readme markdown file. I used the generated readme in a modified way on my landing page as well. As it is markdown, which you are now a pro at, simply adjust it to your liking. Then add it to the about.md file, and on your next deploy, your “About” tab will look amazing!

Curriculum Vitae

Similarly, especially if you would like to use your website to apply for jobs, it makes sense to add a CV to your site. I opted to add another tab (simply add a cv.md file under tabs), which contains my CV in markdown. This is a particulary convenient feature. I have always felt the means of conveying my experiences in a few words very limiting. While it may be a good practise at being brief, employers hardly get a good understanding of your skills that way. Hosting your CV on your website has a few advantages. For example, to elaborate on your experiences, you can simply provide a drop down menu in each experience, where you go into further detail. Therefore, you avoid cluttering your CV, while still being able to add more information. Secondly, you can add links to posts or projects you have done, allowing the employer further insight into you, your skills, hobbies and experiences.

Creating a CV is a matter of simply designing another markdown file. It took some time for me to be satisfied with it, so take yours. This primer is based on my CV and should give you a starting point, feel free to make use of, expand and modify it!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

---

icon: fas fa-solid fa-file-lines

order: 2

---

# <i class="fa-solid fa-graduation-cap"></i> Education

---

<i class="fa-solid fa-location-dot"></i> Example City

**<span style="font-size: x-large;">Example School</span>**

*yyyy - yyyy*

Short description

# <i class="fas fa-laptop"></i> Work Experience

---

<i class="fa-solid fa-location-dot"></i> Example City

**<span style="font-size: x-large;">Example Company</span>** *mm yyyy - mm yyyy*

<span style="color:#3396FF;"> *Position* </span>

Short description

<details>

<summary>Drop down for more details</summary>

<br>

Surprise!

</details>

# <i class="fa-solid fa-icons"></i> Other Expertise

---

**<span style="font-size: x-large;">Interesting Instrument</span>** *since yyyy*

Basically a virtuoso.

**<span style="font-size: x-large;">Interesting Area of Knowledge</span>** *since yyyy*

Very Interesting

To add other icons, visit Fontawesome, copy the HTML code snippet of an icon you like and simply place it in the text, as I did above. The icon at the very top determines, what icon will be displayed on the tab on the left side bar.

Add a Favicon

A little extra detail to give your site an edge is to add a favicon, the little icon that displays in the browser tab next your site’s name. By default, it is set to the chirpy logo, but you can easily customize this. Head over to this favicon generation site. You can upload any image you like, and will be guided through the creation process. Generate your favicon by selecting Generate your Favicons and HTML code (the path doesn’t matter for now). Download and unzip the folder. All you need from there are the .ico and the .png files (all of them). Simply copy these into your site’s assets/img/favicons folder (create it, if it doesn’t already exist). Delete any previously existing .ico and .png files. And there you go! Build your site and check it out in the browser. Don’t forget to clear your cache, otherwise the old favicon will continue displaying.

Add Comments

In order to let people comment on the posts you create, a few options are available. As we are using a static site generator, we will need a third party commenting service. I am using an open source commenting tool called Utterances, which uses GitHub issues to create comments. Outside of the tech world, where readers don’t tend to have GitHub accounts, that may be of a slight disadvantage, as the commenter needs to log in using GitHub, but the ease of use outweighs that disadvantage.

Technically, Chirpy lets you use Utterances natively. For some reason, that didn’t work for me, so I chose a different way.

The first thing you should do, is add a folder to your site’s root directory called _layouts. In there, create a file called post.html. This will tell Jekyll how all your posts should be layed out. In gem-based Jekyll themes, this is already included inside the theme’s gem file in your website’s directory, hidden from view, as you’re normally better off not messing with it. But not today. By creating a new one, Jekyll will override the default and make use of that one instead. You can find the hidden _layout folder with the following command:

1

bundle info --path jekyll-theme-chirpy

Change directory into that path. You will now see a _layouts folder. Inside, you will find the post.html file. As we don’t really want to change anything apart from adding comments to the end of the post, simply copy its contents into your newly created post.html file.

To add the commenting ability, head over to utterances.es. Simply follow the instructions listed there. This will generate a short HTML script tag that you can copy and paste right to the end of your new post.html file. From now on, your post’s default layout will contain a commenting framework at the end.

Next, install Utterances on your website’s GitHub repo by opening GitHub Marketplace from the left sidebar and search for Utterances. Select the repo you would like to use it on, push your changes to GitHub, and you’re done!

Now, whenever someone comments on a post, Utterances will create an issue in your websites GitHub repo for that post and let people comment on it.

Setting Up Google Analytics

Wanna know how massively popular your website has become? That’s actually pretty easy to find out (apart from checking the comments). You can simply add Google Analytics to your site, which is easily configurable in the _config.yml file.

First, set up a Google Analytics account. Click on “Get started today” and follow the instructions. It will ask you to create a property name somewhere along the way. A property is basically a folder, where you can view all the tracking data for your specific website. Once done, you have created a web stream, through which Google Analytics can receive traffic data from your site. The only thing left to be done now, is to copy the stream’s measurement ID into the according place in the _config.yml file.

1

2

google_analytics:

id: # Paste measurement ID here

This measurement ID should be displayed to you right after you created the web stream. If not, click Settings in the bottom left corner, then under Property Settings → Data Collection and Modification → Data Streams. If everything went as expected, you should see user data from your website, which you can view under the “Home” tab. If you don’t have insane amounts of traffic like I do, go ahead and visit your own website to see if Google Analytics captures it (definitely not what I did).

Troubleshooting

While most problems I encountered were already discussed above, here are a few issues I stumbled upon, that happened to me now and again and that I would like to highlight. If you encounter any other issues, let me know in the comments. Chances are I have already encoutered those as well and forgotten to add them here.

The website is not displayed properly

Make sure:

- the repo is public.

- your URL is set correctly in

_config.yml.

A post is not displayed properly

Make sure:

- your post’s name’s format is as described.

The changes you made have not been applied

Make sure:

- you actually pushed your changes to GitHub

- GitHub has already finished deploying your site. This can take a few minutes.

Your favicon is not displayed

- Clear the browser cache, or try in a different browser.