Programming Good Weather

What I Learned In This Project

- How to use geographical data in code

- How to use meteorological data in code

- How to create a basic utility function

- Leveraging environment variables for sensitive data

- Increased my Python Skills

- How to create and host a web-app using Streamlit

- To better estimate the time it takes to develop something

Summer? Hardly!

Recently, I’ve been somewhat unsatisfied. It’s summer over here in Germany. At least its supposed to be. I grew up in South Africa and was therefore a sun-spoilt child. However, I only realized this once I moved to Germany for my studies. All the more unfulfilling that about 95% of days since the summer started were the opposite of warm and sunny. On top of that: Aachen, where I live, is known to be one of the rainiest cities in Germany (at least the locals like to think so). Whenever I saw the weather forecast, there was some place around with summer vibes, but it was not here. The logical conclusion: Leaving home = better weather. This is most likely untrue, but there is always (usually) a place where summer has actually arrived within a certain radius, it’s just got to be found. I thought: the next time the weather is so terrible on a weekend, I’m outta here! I’m gonna check the weather forecast for the best weather in the area, and spend the day there.

Being a somewhat tech-savvy person (at least I like to think so), of course this idea didn’t spend long in my head before I thought: It’s much easier to just write a program to search for such a place! Just somehow pass my location into it and let it search a radius of 50km for the place with the most sunshine and the least rain! So that’s what I did. Check it out.

And to be honest, that is pretty much what my program does. However, implementing it wasn’t quite as straightforward as the pseudocode I had thought out in my head. But I’m grateful for it, because I learned many new things. Things that might even become useful at a later stage of my autonomous systems engineering career. And maybe there is a thing or two that I can pass onto you. So keep reading!

Chosing a Language

Not a humongous amount of thought went into selecting a language, it seemed quite obvious to me from the get-go: This whole project was supposed to be a 3-hour endeavour that needed to get some data from the internet and calculate some things from it (Side Note: The project is still not entirely finished and I have a nagging feeling that I will never be 100% happy with it). Also didn’t need to have a short runtime. And I also wanted some sort of user interface to go along with it.

Then I remembered that I had recently made use of a Python library by the name of Streamlit for work. Streamlit enables you to quickly and simply write up web-apps using interactive elements, including inputs that can then be processed by the program. Exactly what I needed, plus, Streamlit even lets you host the web app for free on their cloud, so I would be able to find a place with nice weather from whatever miserable location I was in at any time!

So Python it became. Easy to use and fast to get going with, plus Streamlit, decision made.

Retrieving Location Data

First thing’s first: to find the best weather in places, you need to find places. For me, this meant: determining how far I would like to travel on a given day, from my location to the location with the best weather. I also didn’t really feel like ending up in a place where only 2 people lived and the most exciting thing to do is watching the wheat grow, usually at least.

So I first needed the program to find my own location and then all locations within a given radius around my location with a certain population. Of course there is no better place to look than OpenStreetMap.

Having never retrieved anything from the internet before (in a program, I mean), I had no idea how to go about it, I only knew it was possible. Good thing that it’s not that difficult. OpenStreetMap has an API called Overpass, which lets you place queries to OpenStreetMap and returns some geographical data. Using this, retrieving OSM data looks as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

import requests

[...]

lat = 33.9221

lon = 18.4231

overpass_url = "http://overpass-api.de/api/interpreter"

overpass_query = f"""

[out:json];

(

node["place"="city"](around:{radius_km * 1000},{lat},{lon})["population"];

node["place"="town"](around:{radius_km * 1000},{lat},{lon})["population"];

node["place"="village"](around:{radius_km * 1000},{lat},{lon})["population"];

);

out body;

"""

try:

response = requests.get(overpass_url, params={'data': overpass_query}, timeout=5)

except requests.exceptions.Timeout:

st.error("Searching for towns took too long. Please try again.")

st.stop()

By the way, if anyone feels the need to roast my code…please drop a comment at the bottom of the post, I’d genuinely be interested in feedback 😁

Now, the data returned by the Overpass API is not entirely consistent. Some locations have a simple integer as a population count, some contain something along the lines of “20 312 in the year 2001”, and some just decide to speak french. So some parsing of the population data was necessary to filter out the actual number. Being a Python expert (not really), I jumped right onto the regex hype train.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

import re

[...]

def parse_population(population_data: str) -> int:

match = re.search(r'\d[\d\s]*', population_data)

if match:

cleaned_population_str = match.group().replace(' ', '')

population = int(cleaned_population_str)

else:

population = 0

return population

This regex (regular expression) finds any combination of elements that start with a digit (‘\d’), followed by a combination of more digits or whitespace characters (‘[\d\s]*’). In the above example, this would extract ‘20 312’ from the population string. In the following if-clause, any spaces are removed, yielding ‘20312’. Finally something we can work with.

Streamlit

Take note of the st.error() and st.stop(). The former is Streamlit’s way of displaying error messages. The latter causes the rest of the script execution to stop. The way Streamlit works, is that whenever the user interacts with the user interface, the script is re-run with the new data. This is necessary to remember when designing the code, as this can cause variables to be reset or display elements to be removed. In my case, whenever I changed any of the slider values, the entire app was reset and all entries had to be redone. That is what the so-called Streamlit session state is for. This is basically a dictionary into which you can write any variables neccessary across script re-runs. The session state can be accessed just like any other dictionary:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# Write user coordinates into session state

st.session_state['user_lat'] = user_coordinates['lat']

st.session_state['user_lon'] = user_coordinates['lon']

# Re-run script

map_center = [st.session_state['user_lat'], st.session_state['user_lon']]

# Check if a variable is present

if 'fetched_user_locations' in st.session_state and \

st.session_state['fetched_user_locations'] is True:

determine_user_coordinates()

# Remove a variable from the session state

del st.session_state['user_lat']

# Clear the entire session state

st.session_state.clear()

Retrieving Weather Data

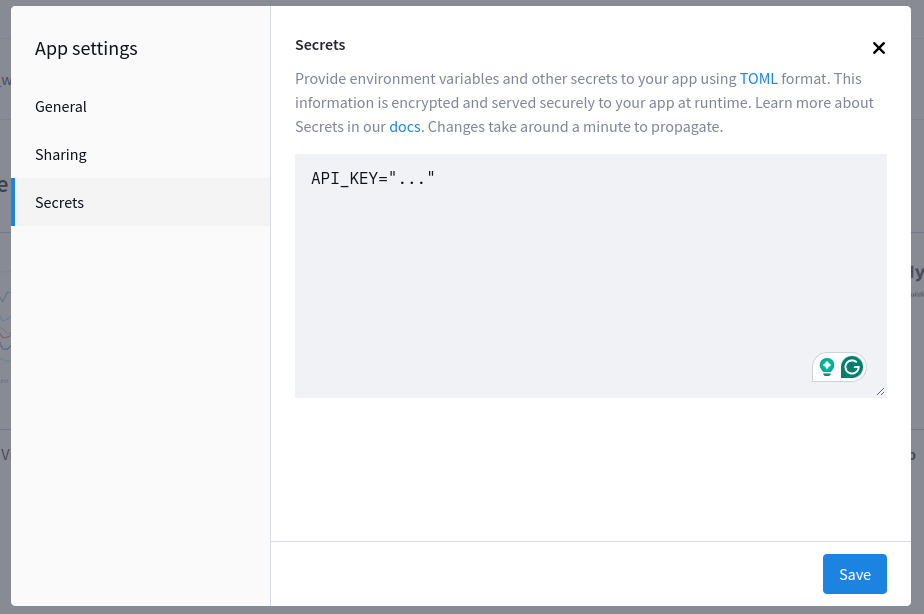

Now that I had my location and some possible locations I could visit, what was next? Well, to build a best-weather-finding app, I needed weather. Apart from that, I needed somewhere to get data about the weather from. Enter: OpenWeatherMap. Like any other source of weather data, it provides the current weather and forecasts, among other things. But most importantly, it provides an API, enabling the retrieval of the weather data into a program. It’s as simple as signing up at OpenWeatherMap. I was sent an API key via email which I could use to make requests to OpenWeatherMap via my program. Being the wise person that I am, I immediately set this API key as an environment variable in my Python virtual environment and accessed this from the code, to avoid having sensitive data there for everyone to see (and especially didn’t check this into Git):

1

2

3

import os

[...]

api_key = os.getenv('API_KEY')

Actually, I did not do all of those things, and shortly later noticed what I had done. Well, at least that won’t ever happen to me again 😆 Take that as a warning not to make the same mistake! So after creating a new, clean Git repo, all was well again. The cool thing is, if you host your Streamlit app on the Streamlit cloud, they provide a similar mechanism for creating environment variables called Streamlit secrets. More on that later. So in order to retrieve weather data from OpenWeatherMaps using the securely saved API key, we can simply make a request from the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

import requests

[...]

# For every location within the user's selected radius:

lat, lon = location[1], location[2]

url = \

f"http://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/forecast?lat={lat}&lon={lon}&appid={api_key}&units=metric"

try:

response = requests.get(url, timeout=180).json()

except requests.exceptions.Timeout:

st.error("Retrieving the weather data took too long. Please try again.")

st.stop()

I know that is a long timeout, but depending on what the user enters, the app has to search pretty much all cities, towns and villages in a 100km radius and get weather data for it. That may or may not take some time, so when trying the app, please be a little patient 😌

The result of this request is a dictionary with all possible weather data you could want. These include temperature, wind, rain, humidity, visibility, etc., and all that for every three hours for the next five days.

Calculating the Weather Score

So now we have everything we need to find the very best weather around. The question is: how do we make use of all this data to determine in one value the best location to go? Of course, being someone who dabbles in (and will build his entire career on) autonomous systems, I had heard of utility functions before. A utility function is a function that assigns utility values to … things. In my case, this function would assign utility values to towns based on their weather: better weather = higher utility. Having never actually developed a utility function before, I thought I’d just give it a shot off the top of my head. I started by assigning utility values to the temperature, wind and rain data points returned from the OpenWeatherMap API. These were not very fine grained, but good enough for now:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

def calculate_value(temp: float, wind_speed: float, rain: float) -> Tuple[float, float, float]:

if temp > 25:

temp_value = 1

elif 20 <= temp <= 25:

temp_value = 0.5

else:

temp_value = 0

if wind_speed < 5:

wind_value = 1

elif 5 <= wind_speed < 10:

wind_value = 0.5

else:

wind_value = 0

if rain == 0:

rain_value = 1

elif rain < 5:

rain_value = 0.5

else:

rain_value = 0

return temp_value, wind_value, rain_value

This was done for every 3-hour weather data point. These were then added up and normalized over the day that the user entered, in order to gain an average score between 0 and 1. As you may have noticed in the app, you were able to input your preferences concerning which of the weather parameters was the most important to you (rain, temperature, wind). These were also normalized to add up to 1, so that a final weather score for the day could be calculated while taking them into account, weights referring to the entered preferences:

1

2

3

total_score = (weights['temp'] * norm_temp_value +

weights['wind'] * norm_wind_value +

weights['rain'] * norm_rain_value)

Hosting My App on the Streamlit Cloud

As mentioned, Streamlit lets you host your Streamlit app on the Streamlit community cloud for free. It’s really simple too, you simply have to connect the GitHub Repo where your app is stored to the cloud and are ready to go. This also means that whenever you update or change anything, it’s a matter of refreshing the app on the cloud, which will automatically re-deploy it with the new code.

To deploy your app, head over to the community cloud, click Get Started and Continue to sign-in. Here you can log in with GitHub or Google, or with a new account. I suggest signing in with GitHub, as that will immediately link Streamlit with GitHub. Once signed in, click Create App in the top right corner and follow the prompts:

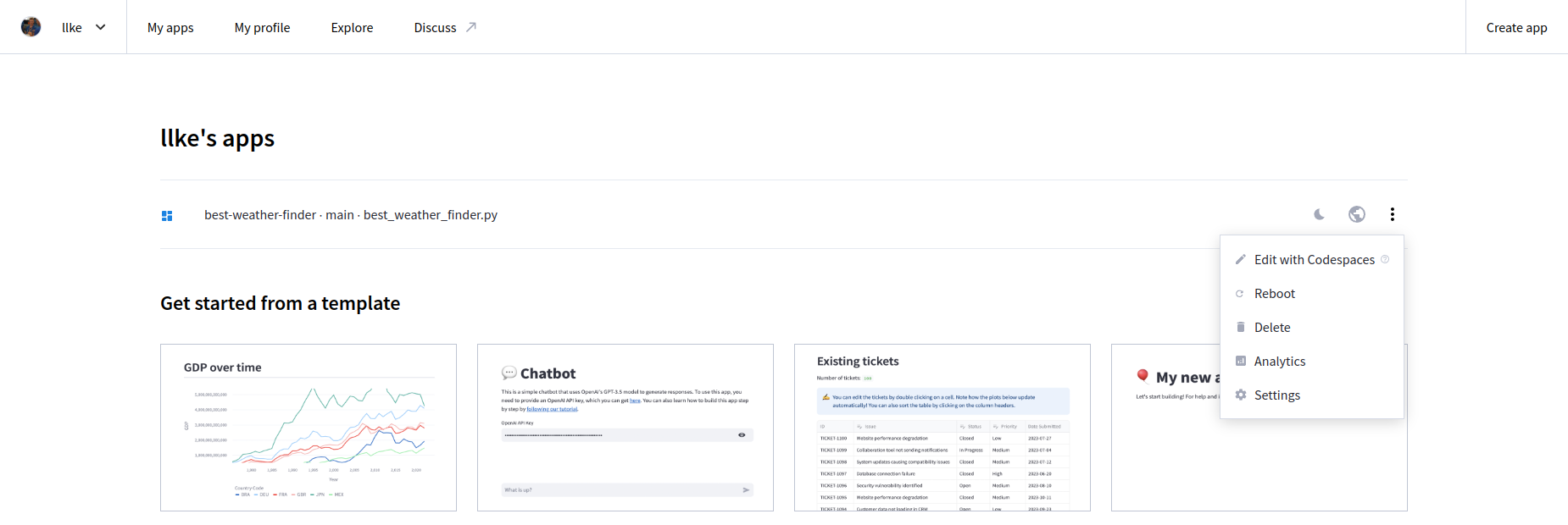

Et voilà! Your app is up and running! You should now be able to see it:

If you push any changes, simply hit the Reboot button. Now remember earlier we had those local environment variables in our Python virtual environment to store the API key needed to access OpenWeatherMap? We can also store them directly in the Streamlit cloud as a so-called Streamlit Secret. To do that, click Settings on the drop down menu next to your app, as in the image above, then select Secrets on the left. Then add any sensitive data in here in the following form:

These can now be used in exactly the same way as in the local code, no changes required (provided the environment variables have the same name as in your local repo)!

Conclusion

So there we go. This might actually have been the first bigger coding project I did for myself. I had great fun and learned a lot. While this app itself might be more of a gimmick, many of the skills I learned here might likely prove useful in my autonomous systems engineering endeavours. Such things as using geographical and meteorological data in code, which autonomous systems can leverage. I learned how to quickly prototype ideas using Python, which makes this increadibly easy. I learned not to throw sensitive data into Git, which is useful wherever I go, no matter if autonomous system or good weather. And that developing takes a lot longer than is initially expected. I sort of knew that. And getting it working took only a few hours. But the fine tuning at the end, the debugging and making everything work reliably…There’s that overplayed rule called Pareto’s Principle, where the first 80% of something take 20% of the time, but the last 20% take 80% of the time. Can confirm.

I hope you also had some fun playing around with my app. If there’s anything you’d like to add/improve/elaborate upon, please go ahead! And I’d be greatly happy about any feedback or opinions you have, so feel free to check out the code on GitHub, or simply drop me a comment.

I hope you have a sunny day, wherever you end up!